[Long read…]

I haven’t been feeling well recently. An ongoing fatigue illness. Which, as I mentioned last month, has meant I have had to temporarily stop putting new music on this site (because all my music-making has to be focused on making money, which is not what this site is about).

This led me to spend a lot of time researching what the health problem might be: talking with my GP, reading books, reading scientific papers, watching lectures on YouTube. And after a bit of trial and error, I think I’ve located the problem and have felt back to normal for a couple of weeks now.

And it was an eye-opening experience for me, because up to now I had felt that medicine was a topic I wasn’t even going to try to understand. Because, I felt, ‘a little knowledge is a dangerous thing’ and if you don’t have the wider understanding of how the systems of the body work you’ll almost certainly leap to unhealthy conclusions.

But now I’ve changed my mind. The science of the body is fascinating. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with trying to understand it, and even self-diagnose where things might be going wrong, so long as you have medical professionals that you trust who you can leave the last word to. So much of good health comes down to good lifestyle, and that means understanding what makes a good healthy lifestyle and why. And you do yourself a favour by trying to do that. (Even if you still intend to get shitfaced at least once a month, as I do.)

And it occurred to me, maybe it might even be something I could write about on my website. (To be honest, a good deal of what I write is really for my own benefit, as a reminder that ‘this thing is important’.) “It has nothing to do with music though,” my brain replied.

But actually, it does. This health problem has stopped me from being able to make the music that I want to make. And it has made me considerably less happy. However, I have always been the kind of person that who says “I am going to try to understand the problem”. I find most problems can actually be understood, and when they’re understood they can be solved, or at least worked around. And for the problems I can’t understand… well, at least I tried. And even then, who knows – maybe it’s not too late. Maybe a new discovery tomorrow will change everything.

So, to try to prove this point, I’m going to write about the problem that’s been affecting me. And I’m also going to write about it here because one of the first things I learnt was that it is frequently misdiagnosed, and so I think there’s a possibility it could be useful to other people.

But first, a disclaimer:

I am not an expert, or even a particularly well-informed amateur, on the subject of medical science. What I’m writing here is in the broadest of brush strokes, with much crucial detail omitted. And I could fill this article with tons of links and/or footnotes to back up everything I write here, but this clearly isn’t a scientific paper and I don’t want to imply that it is trying to be. Pretty much everything I write is my summary of the YouTube videos of academic talks that I’m attaching here (particularly the last one), so if anything I write contradicts those videos… well, you know which one of us made the mistake. (And do feel free to message me and point it out if you feel it’s a particularly serious one.)

So, are you sitting comfortably?

The Hygiene Hypothesis

A curious medical phenomenon of the last 70 years is that the global number of deaths by infectious diseases have dramatically fallen, just as autoimmune diseases have dramatically risen.

No longer are the large majority of us dying from diseases like smallpox, polio and malaria, in which harmful micro-organisms (‘pathogens’) get into our bodies and lead to death within months or even days. Now we as a species are much more likely to die slowly from diseases in which the body mistakenly believes it’s fighting pathogens, and ends up destroying its own tissue in the process. Diseases like multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes and Crohn’s disease. (And potentially allergies, chronic fatigue illnesses, Alzheimer’s disease and even obesity and certain types of cancer, although I think all of these are more contentious.)

One medical explanation for this is known as the Hygiene Hypothesis. Originally, the theory was that the cleanliness of the modern world was actually preventing infants from developing adequate immune systems, by denying them exposure to small doses of pathogens. Fairly recently, however, this hypothesis has been developed, and now the consensus is that the problem isn’t a lack of pathogens: it’s something else entirely. It’s about a whole ecosystem living inside us, which until recently was barely acknowledged, let alone understood.

We contain multitudes…

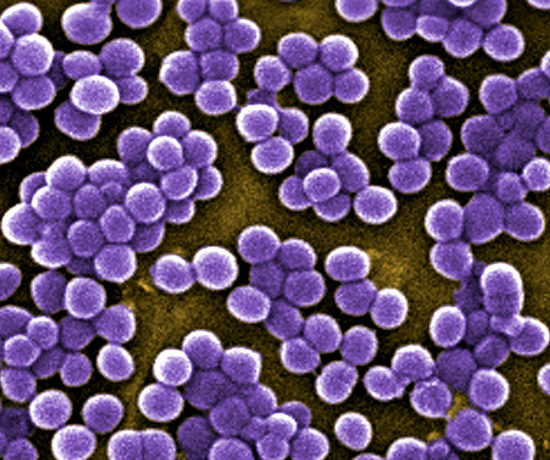

We have independent micro-organisms living inside us, that are not technically part of the body itself. Sometimes these microbes are pathogens (which the body fights, usually with success), but many more are actually friendly. Many… many many more, in fact. Your body has around 100 trillion microbes, about 10 times more than the number of actual cells in the body. Numerically, you’re kind of more microbe than… you.

The discovery of antibiotics like penicillin led to the realisation that many diseases were due to these tiniest of critters, and so the focus became how best to destroy them. It’s only in the last few decades that medical science has come to realise that this was a mistake. A rather big mistake, in fact. Because these microbes are more than just ‘friendly’, they’re essential to the proper functioning of our bodies.

… but barely 2 genes to rub together

Quick tangent back to the year 2000, and the mapping of the human genome. Many scientists were amazed at how few genes we humans had. Between 20,000 to 25,000 protein-encoding genes at the last count. Which may sound like a lot. But to put it into perspective: an earthworm has only slightly fewer. Whereas a plant like wheat has over 150,000. How can we be so complex a species, and yet have such a small number of genes? And how come we all have 99.9% of the same genes as any other human?

Well, that may be true, but we share only around 10% of those 100 trillion microbes with other humans. And these microbes have their own genes, and there is research that shows that those genes affect how our bodies develop, especially when we come to develop our immune system.

How microbes help to make our immune system

In our first 1,000 days of life, it is the microbes in our body that build up a sort of a database of what should be considered part of the body and what should be considered a pathogen. If this is done correctly then our bodies should always be able to detect real pathogens quickly and deploy its own arsenal (‘antigens’) to fight them. If isn’t done correctly, however, the body gets confused. Paranoid, even. Everything starts to look like a pathogen, and antigens can be deployed left right and centre to tackle them. With loss of our precious body tissue as the collateral damage of this phoney war.

So it seems that it’s about so much more than static genes defining how our bodies react (although that is still considered a major part of the equation). Now it seems that our bodies are in constant dialogue with these microbes, determining what inside of us is friend and what is foe.

And if medical science could understand the language that this dialogue takes place then, potentially, it could cure a whole host of autoimmune diseases.

(And I’d like to take a moment for another quick tangent: movie fans might be down on George Lucas for making The Phantom Menace, but the joke’s on you, because it sounds to me like ‘midichlorians’ are actually a Thing!)

So it’s just a simple case of studying these microbes, right?

Well, to paraphrase Dr Fasano’s analogy from the video at the bottom: if you compare the taxonomy (i.e. Species within a Genus within a Family, an Order, a Class, a Phylum, a Kingdom and finally a Domain) to the cosmos, and pretend that the Domain is the universe, the Kingdom is the milky way, the Phylum is our solar system, the Class is the Earth, the Order is your continent, the Family your country, the Genus your nearest town and your Species is your home… our understanding of microbiota is currently at around the Solar System level. And the stuff we need to study is on the scale of your home. And even then, we don’t just need to study the microbes themselves: we need to study the language that they communicate in. Because that’s what is telling our immune system to attack pathogens.

Or to go on a roaring rampage of irrational revenge against its own tissue, as the case may be.

Stuff that messes it all up

There’s a lot that can disrupt that immune-system-building in those crucial first 1,000 days of life. There’s the usual suspects of excessive drinking/smoking/drugs/etc when the baby is in the womb. But there’s also the possibility that, once born, the baby gets an infection and needs antibiotics. That seriously messes with the development of the immune system, but… what can you do? Infections kill. Another factor that can have a surprisingly powerful effect is whether the baby is born by caesarean section. It seems that a lot of these essential microbes are passed directly from the mother: when the baby is in the womb, from breast milk (which contains some sugars which the baby can’t digest but the baby’s microbes can), and also from the vaginal canal. And once again, immunity-building gets messed up when vaginal delivery isn’t an option (but, again, it’s sometimes unavoidable).

So that’s microbes for you

Now, before I got recently ill I didn’t know anything about this stuff. But I was behind the curve, because a lot of popular science communicators have been getting excited about microbiota for some time now. If you’re interested in finding out more about it, the book everyone is talking about (which I’m about to read but haven’t started yet) is I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong. And here is a recent lecture he gave, if you want a long intro to that book:

Although there’s also a shorter TED talk by microbiome expert Rob Knight if your day is busy:

But is there another culprit for the rise of autoimmune diseases?

So, thanks to advances in modern medicine, there are a lot of people walking around today with very trigger happy immune systems, that freak out when they eat certain foods or breathe certain particles or get certain drugs injected into their bloodstreams.

But there might be another major factor at play here, as well as the microbes. And it’s all about guts. And our old friend wheat.

The trap doors in our gut walls

The gut is a vital organ. I mean… you knew that. But it is the part of the body that extracts everything that the body needs (other than oxygen) to survive. An earthworm is basically just a gut. But being this sort of gateway to the outside world, the gut is also the most vulnerable to infection. Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (of ‘Hippocratic oath’ fame) is believed to have said “All disease begins in the gut”. And though that might not be the view of the medical profession now, it at least highlights this vulnerability.

But the body has a way to deal with this. In order for the gut to determine whether there are any nasties that we might have swallowed that need to be attacked, it uses a sampling approach which has only relatively recently been discovered: it opens ‘doors’ known as Tight Junctions in the wall of the gut, and it lets random samples of gut contents directly into the bloodstream. It does this in very small doses, so it can build up a picture of what’s going on in there.

Accidentally opening these doors

However. Here’s the thing. The body creates a protein called zonulin that it uses to open the tight junctions in the gut walls. But, as humans have become ever more resourceful and have expanded their diets, there is a food — or rather a protein contained in a food — which mimics this zonulin effect. That protein is called gliadin, and it is found in gluten. Which is found in wheat, rye, barley etc.

Now, as I understand it, gluten has this negative side-effect with absolutely everybody: it stimulates the gut walls to open up and let too much gut content into the bloodstream. BUT… this is actually not a problem for most people. The immune system just takes care of it, by carefully searching out anything that shouldn’t be there and neutralising it.

Where it really becomes a problem (for people like me) is if you have a hair-trigger immune system (thanks to the microbe problem I mentioned earlier), that sees all of this foreign matter let through the gut walls into the blood stream as a massive attack of infectious diseases. And instead of carefully picking out the pathogens, it wheels out the heavy artillery. Which results in inflammation.

And the inflammation bit I find particularly interesting. I’ve heard this problem called a ‘chameleon disease’, because once there is inflammation in the blood stream it can go… wherever the blood in your body goes. Which is pretty much everywhere. So you can get aching in your joints, in your muscles, problems with pretty much any of your organs, and it can even affect your brain. This is a problem which is very hard to diagnose, because the symptoms you feel will probably be nowhere near the gut.

So what can be done about this?

Well, for those who have coeliac disease, or just those who are gluten sensitive, it’s a simple case of cutting out gluten. This is particularly important for coeliac disease, as gluten doesn’t just cause an unnecessary and exhausting immune response: it actually damages the gut. (The gluten-free options are really pretty good now, though!)

And in the future, hopefully, when more is understood about the microbiota, it will hopefully be possible to get bespoke medication to make sure you have the right diversity of microbes, and thus your immune system stops freaking out.

But in the meantime, the best way to look after your microbiota is what the doctor always orders: enough sleep, enough exercise, and especially the right balance of food. (I’ve heard various experts recommend the ‘Mediterranean diet’ — I’m wary of anything with the word ‘diet’ in the title, but I’m assured that this is actually like the Pirates’ Code… more like guidelines.)

But… wine is okay, right?

Yeah, weirdly it is. Not just ‘okay’ but almost mandatory, according to some interpretations of the Mediterranean diet.

Although when it comes to whether things that you like are good for you (excluding things like gluten) I find it’s best to (a) keep having them and (b) wait until your social media feed features an article saying it’s good for you again.

And the moral of the story is…?

Pasta is fucking infuriatingly tasty. But hey ho…

(This lecture is the least accessible, but the one I found most fascinating…)

Leave a Reply